Heavy Battery, Royal Australian Artillery, Rabaul

Born: 5 June 1905, Walkerville, South Australia

Prisoner of War: 1942 – 1945

Died: South Australia, September 1974

Information provided by: Helen Moulds (daughter) & Sarah Gillespie (granddaughter)

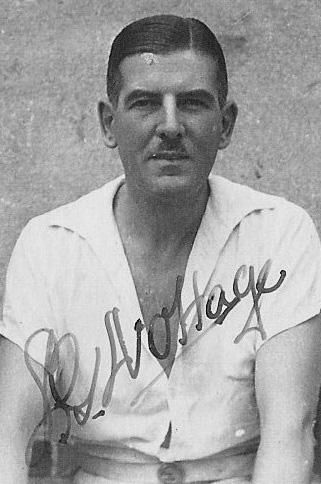

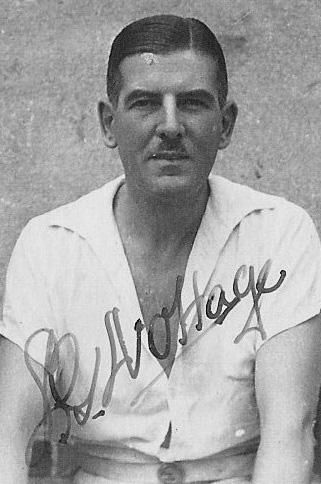

Captain Stewart Gordon Nottage

by Sarah Gillespie (granddaughter)

Captain Stewart Nottage was born in the inner Adelaide suburb of Walkerville in June 1905. He was educated at St Andrew’s School and then commenced work with Adelaide Electric Supply Company. Stewart was a member of the local militia based at Fort Largs.

He married Miss Mollie Snelling of Largs Bay in November 1934 and their only child, a daughter Helen, was born in June 1936.

Stewart enlisted on 25 February 1941 and he left Adelaide on 26 February 1941, one of a party of Coastal Defence Gunners, who with Tasmanians and Victorians assembled at Queenscliff prior to leaving Australia. The group embarked on the troopship Zealandia from Sydney on 18 April 1941, knowing that their destination was Rabaul. After an eight-day voyage escorted by HMAS Adelaide, they dropped anchor in Rabaul Harbour at 3pm on Anzac Day, 25 April.

Stewart soon realised that Rabaul was surely the “Paradise of the Pacific”. He was involved in the building of the new camp at Praed Point, about six miles from Rabaul where two six-inch coastal guns had been positioned to protect the entrance to Rabaul harbour. This necessitated the construction of a road which encircled the base of Matupi Volcano, which was at that time inactive.

Following the declaration of war with Japan, RAAF planes commenced operations and the Japanese followed with their own reconnaissance planes over Rabaul. Stewart remembered their Christmas dinner of 1941 being interrupted when the alarm was sounded as a large four-engine flying boat* flew over. The reconnaissance raids continued until the first bombs fell on Rabaul on January 4, 1942. On 20 January, 109 Japanese carrier- based aircraft attacked Rabaul and the shipping in Simpson Harbour. (*Editor’s Note: These aircraft were almost certainly Kawanishi H6K flying boats – Allied code name “Mavis” – used by the Imperial Japanese Navy for reconnaissance).

Stewart recalled an intense bombing raid on the battery at Praed Point on 22 January 1942 which caused a landslide that buried the guns and killed 13 of his men. Prior to the invasion, he was senior officer of the personnel who withdrew from the area. The Japanese invasion force comprised a vast deployment of air and sea resources, together with over 5,300 infantry, completely overwhelming the approximately 1,400 numbering Lark Force. The 1300 men of Lark Force without field artillery or aerial support could offer little resistance to this overwhelming force, but after a period of ten days and nights spent in the jungle endeavouring to make contact with other escaping troops, Stewart was captured at Taliligap Taulil mission on 2 February and was taken to Rabaul where he “lost all except wallet and glasses” during his initial search. Stewart’s wallet contained money in notes and photos of his wife and daughter and home, which were to be a great comfort to him in the years to come.

Conditions as a POW in the camp at Rabaul were poor, the prisoners being organised into work parties by the Japanese to load and unload supplies at the wharves. On 29 April 1942 the Japanese Navy took over the camp from the Army and food rations were cut. In May and early June, US and RAAF planes were frequently seen by the prisoners over Rabaul attacking Japanese shipping.

Stewart writes that the ‘parting of the ways’ came on 22 June when ‘approximately 300 civilians and 800 troops were separated from the officers (numbering 60) marched out of camp to the wharves embarked on a vessel in the harbour.’ Their Japanese captors refused the officers’ requests to allow them to accompany the troops. Little did Stewart and his fellow officers know that ‘this was the last ever to be heard of these gallant men’ with the sinking of the Montevideo Maru off the coast of the Philippines on 1 July 1942.

Two weeks later, the remaining officers, with only 10 minutes warning, were ‘ordered to prepare a package of personal belongings’ in readiness to embark on a vessel, the Naruto Maru. After embarkation the group was moved to the aft hatch and ordered down into the hold, where to their great surprise, they found the six army nursing sisters who had accompanied them to Rabaul, 11 civilian and missionary nursing sisters and Mrs Bignell, a local plantation owner. The ship sailed from Rabaul 24 hours later on 6 July 1942, and arrived in Yokohama on 14 July 1942.

After three days of quarantine and interrogation, Stewart and most of his fellow officers were sent to the Zentsuji POW camp on the island of Shikoku where they were held for almost three years until they were transferred to another POW camp, Nishi-Ashibetsu, at Hakodate, on the northern island of Hokkaido in June 1945.

Stewart’s wife and daughter Helen were notified that he had been captured by the Japanese and had been transported to a POW camp in Japan in September 1942.

Following the Japanese surrender, his wife and daughter in Adelaide received a telegram from Stewart dated 21 August 1945 expressing his excitement and relief that the hostilities had ceased and that he would be home soon. The prisoners left this camp on 11 September 1945. Stewart arrived in Manila three days later. He sailed on the HMS Formidable to Sydney and finally arrived in Adelaide to be reunited with his family on 16 October 1945.

A large collection of Stewart’s memorabilia, which includes correspondence, diaries, notebooks, nominal rolls, official documents, photographs, maps and books, is held by the Australian War Memorial (AWM). He kept meticulous diaries whilst a prisoner in which he detailed the problems experienced through poor nutrition and the non-receipt of Red Cross parcels in 1944-1945. 1

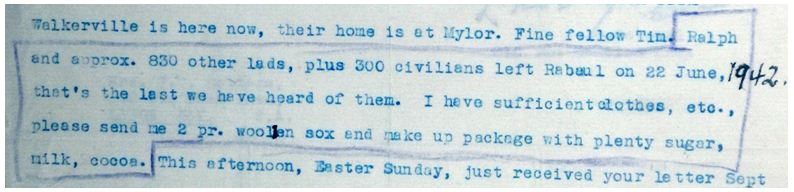

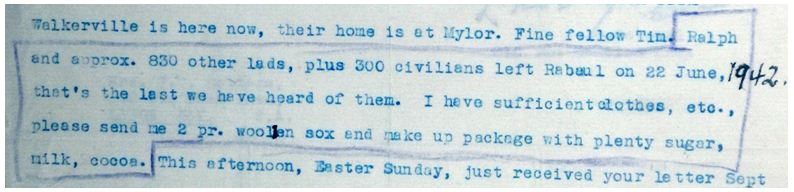

Amongst the correspondence in the collection is a letter written by Stewart to Mollie and Helen dated 17 April 1944, received by them in January 1945, in which he states:

‘Ralph and approx 830 other lads, plus 300 civilians left Rabaul on 22 June 1942. That’s the last we heard of them’.

It would appear that this section of his letter was of interest to military intelligence [see extract below]. The ‘Ralph’ referred to in this letter was Sgt Ralph Codd S14109, also of Adelaide, who was aboard the Montevideo Maru when it left Rabaul on 22 June 1942.

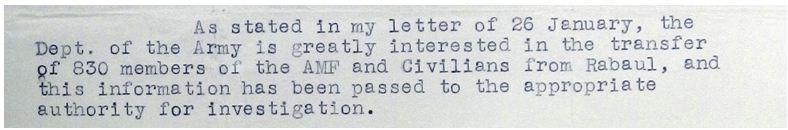

Also in the collection is a letter written to Mollie by the Military Board of the Department of the Army dated 26 January 1945, advising her that censorship had informed their office of the contents of Stewart’s letter to her of 17 April 1944 and that Japanese authorities, despite repeated requests, had failed to provide any information concerning members of the Australian Military Forces who were located in Rabaul. They requested that the letter and photographs be forwarded to them for further examination.

In further correspondence from the Military Board to Mollie dated 15 February 1945, they advise her that Sgt Codd was ‘recorded as missing believed to be a prisoner of war in Rabaul 25 January 1942, but no further information has come to hand concerning him’.

At the end of the war the captured civilians and missionaries, who had survived the war in Rabaul with the Japanese, and the liberated officers in Japan told of the sailing of the Montevideo Maru. Finally on 5 October – nearly two months after the end of the war – the Minister of Territories, Eddie Ward, told parliament of the fate of the ship and the huge loss of life. It had been a long wait for news of the tragedy.

After the war, Stewart returned to civilian life and his former role as an engineer with the Electricity Trust of South Australia, which was established by the State Government as a publicly owned utility in 1946. He remained in close touch with many of his fellow prisoners. For many he was considered a father figure, as at 37 years he was one of the oldest prisoners in the camp.

Stewart died in September 1974. His widow Mollie and daughter Helen were instrumental in the donation of his collection to the AWM after his death. Stewart’s widow Mollie died in February 1989.

Stewart’s daughter Helen Moulds still resides in Adelaide and plans to travel to Canberra for the dedication of the Montevideo Maru Memorial at the AWM on the seventieth anniversary of the sinking of the vessel on 1 July 2012. She will be joined by Stewart’s grandchildren, Sarah Gillespie and Jonathon Moulds (both Canberra residents), and their families, including his great grandchildren Kate, Tom and Annabel Moulds.

1. PR83/189 – Nottage, Stewart Gordon, (Captain), ED, 1905-1974

(Author Sarah Gillespie has been researching her grandfather with the aid of the AWM research centre. She wishes to acknowledge the assistance of Helen Moulds, Marian May and Rod Miller in the preparation of this piece).